to give light to them that sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death

Anthony Oliveira's Dayspring

whereby the dayspring from on high hath visited us;

To give light to them that sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death : and to guide our feet into the way of peace.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son : and to the Holy Ghost;

as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be : world without end. Amen.

- The Benedictus

No one really knows what to do between the end of Good Friday service and the start of the Easter Vigil, more than twenty four hours later. At a death, if you’re close to the deceased, you can occupy yourself with making arrangements. Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimathea, and the disciples did - hurrying the body behind stone before the Sabbath, returning with burial ointments, trying to pick up the pieces of their lives in the awful silence. What I did instead was feel mysteriously rotten and purposeless, read Dayspring, and write.

in the year that King Uzziah died

in the year I was made a postulant to the priesthood

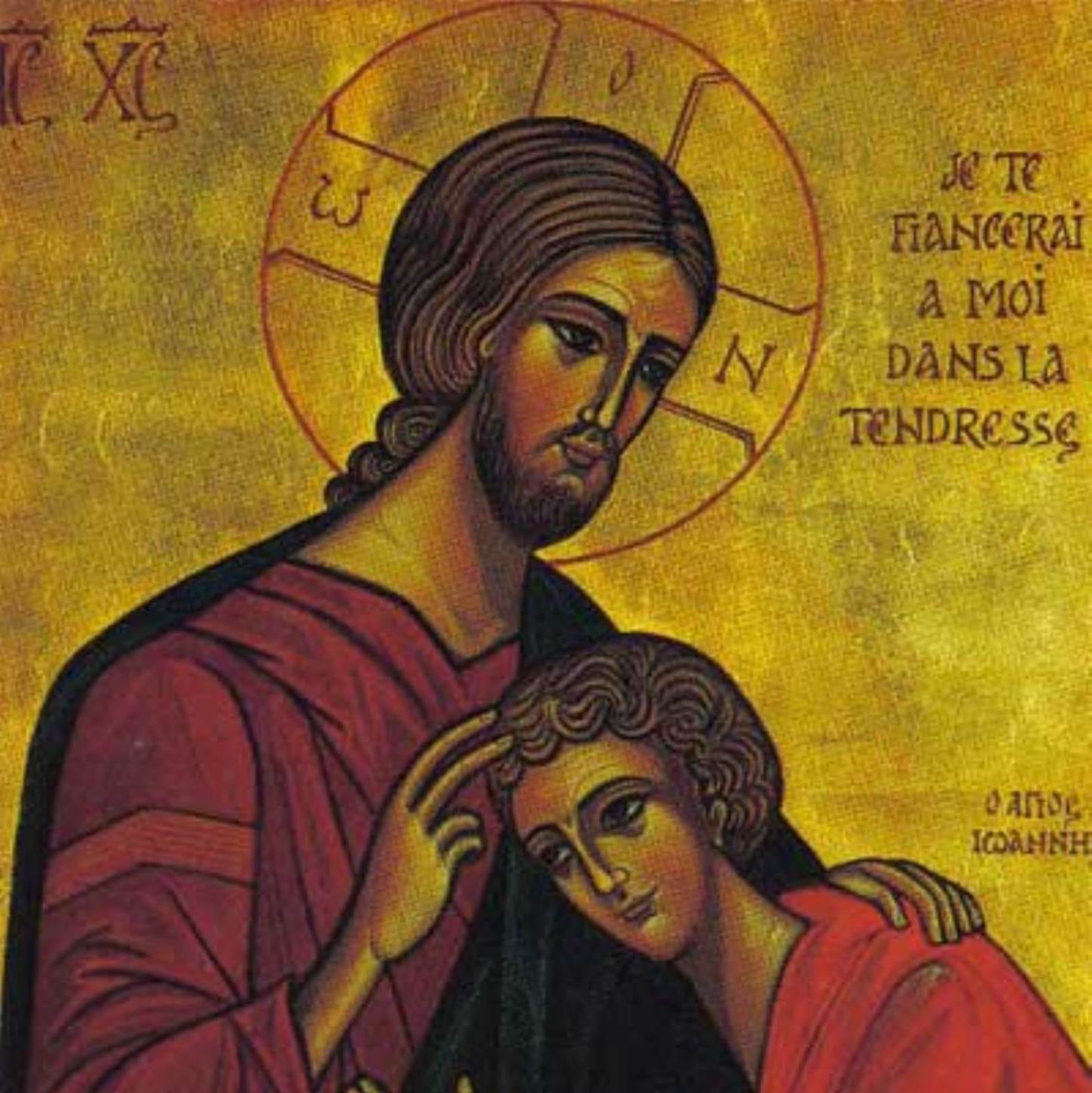

that year, my boyfriend was running a Lent class on the faces of

Jesus – femme Jesus, tarted up Jesus, Buddy Jesus, Jesus of

Montreal. When I had tracked the book – baby’s first advance review copy – down from the

courier depot, I pulled the neat cardboard tab and thought in the

Father Ted voice – Arnold, who’s Arnold? No Father, Ooour Looourd.

Maybe next year, I thought, he could teach this one as well.

Lamb with sex in it. Biff fucks his childhood pal.

We blaspheme because we care.

If there was no meat in it there would be no joy, no point, nothing

to provoke. It wouldn’t matter.

To be a queer Catholic is to say that it matters enough to be a

bad Catholic instead of not being Catholic at all.

Dayspring is a series of page-long linked scenes. It’s a novel in verse, but it doesn’t have a tight plot. It moves seamlessly back and forth between a young adulthood in Catholic school in Toronto and 33 AD Palestine. You are reminded that Jesus is outside time; all time belongs to him, and all ages. John is the passenger experiencing both times with him. It is never explained how this works, but it doesn’t need to be. Dayspring is often more like a book of devotions, which you can pick up and put down at will, marvelling at the richness of each tiny scene. Many Christians choose a Lent book or two as spiritual homework over the forty days. Dayspring accidentally became mine.

Oliveira un-elides centuries of tiptoeing around the relationship between Jesus and John, his “beloved disciple.” Art history treats John the Beloved as a twink; we all already kind of know, but Oliveira writes the sex scenes. This is an obscene book. Do not buy it for your Roman Catholic gran. But that’s exactly the point. Catholics have a tendency to cringe away from the idea of Jesus as fully human as well as fully divine. We talk a good game about the Incarnation, but we’re slippery on the particulars. A “personal relationship with my lord and saviour”? no thanks. Dayspring forces us to look at Jesus’ um, manhood. It forces us to reckon with the cruelty of form and holiness, with a person better at being loving in the general than the particular. Oliveira’s Jesus can be infinitely gracious to humanity as a whole and surprisingly harsh to John, who loves him as a man. He is made to recieve worship, and he sometimes struggles with how to show John he is loved in return.

A lot of books and movies use Roman Catholic aesthetics to make a point. Not all of them carry though as richly and seriously as Dayspring, mixing translations from the writings of mystics and theologians - Simone Weil, Teresa of Avila, Augustine of Hippo - with non-linear poetry and excerpts from the Bible, adapted into dialogue. (Being me, I enjoyed the adaptations of saints and the Old Testament as much, if not more, than the main story.) Oliveira also follows the Protestant red-letter Bible tradition, printing Christ’s dialogue in red. This gives Dayspring the look of a holy text and reminds us that he is undertaking a work of interpretation, not against a long tradition of exegesis but expanding it.

As a fellow ex-Catholic, it is clear that the book is a way of reckoning with a Catholic young adulthood, honouring it, exorcising it, and laying it to rest. Reading it did the same. There have been many renunciations along the way - when I visited an Anglican church, went to an Anglican college, the last time I went and cried to a Catholic priest, when I decided I was done raking myself over the coals of a denomination I couldn’t stay in, when I gave up my Catholic citizenship and was recieved into the Anglican church, and now, finally, being accepted as a postulant for ordination. There may still be more of these endings, but it feels significant that I’m reviewing Dayspring at one of them.

Dayspring (Anthony Oliveira, Penguin Random House/Strange Light), is out April 2